How Your EV Charging Port Can Be Used to Steal Your Car: 3 Critical Flaws

The increasing adoption of Electric Vehicles (EVs) has driven significant security research focused on charging infrastructure and charging stations. While most studies focus on attacking the charging station side through exposed web interfaces, hidden services or Bluetooth functionality, one critical question remains underexplored: how could an attacker hack an EV through the EV charging port?

The charging port is an external interface connected directly to the vehicle’s Electric Vehicle Communication Controller ECU (EVCC). The EVCC handles the complex and critical communication between the EV and the charging station according to the ISO-15118 standard. This ECU serves as a critical entry point to the vehicle as it is directly accessible from the charge port of the vehicle. Yet, unlike the physical doors of the car, the EVCC is not protected by proper security mechanisms. If the EVCC is compromised, an attacker could access critical vehicle components, and expand the attack surface and his foothold inside the EV.

This article examines the full chain of protocols used by the EVCC for high-level communication during the charging process, and the potential security threats that these EV charging infrastructure components represent. In particular, we’ll take a deep dive into three important vulnerabilities found by our research team in the EV charging infrastructure: 1) a vulnerability in V2G communication stack implementations in ECUs and charging stations, 2) a critical vulnerability in an open-source framework that could potentially allow an attacker to compromise a charging stations, and 3) a vulnerability found in the cloud backend for a charging station operator (OCPP). By compromising the EVCC directly through the charge port, these vulnerabilities introduce a new and critical attack vector for vehicle theft.

Understanding the Complexity of the EV Charging Ecosystem

To manage power load balancing between the charged vehicles and to handle the required payment, commercial charging stations need to handle complex communications between the station and the EV. In addition, the charging stations also have to be managed by a backend server for monitoring, software flashing and power delivery management. This complex ecosystem, which includes much more than a simple channel between an EV and a charging station, introduces the need for a dedicated infrastructure as an operating framework.

The Electric Vehicle Charging Controller (EVCC) ECU is responsible for handling the high-level communication between the EV and the charging station. The ECU is located inside the vehicle, and communication with the EVCC occurs through the vehicle’s charging socket, which is exposed and easily accessible. This makes the charging port an attractive target for an attacker, as the communication with this ECU is performed directly from the charging port of the EV. The port itself is concealed by the charging socket door. This makes the ECU more accessible than the OBD II port which requires physical access to the vehicle’s interior.

as a single node in a larger grid operated by a central backend

Hacking EVs and EVSEs From the Charge Port

Communicating with the charging port of a vehicle is performed with dedicated hardware. In most cases, the charging port is not always secured to the same degree as the other elements of the vehicle. Therefore, the initial communication with the EVCC is relatively easy to achieve, especially compared to other ECUs on the vehicle which require in-vehicle access.

The charging port structure varies between different regions in the world, i,e., US, EU, Japan and China. Each region provides a different form factor for the charging socket for AC and DC charging. For AC charging, the Type 2 connector is used in the US (for AC charging), EU and China.

For the DC charging, the variance between the different regions becomes more apparent with CCS1 being used in the US, CCS2 in the EU, CHAdeMO in Japan and GB/T in China.

Communication Between EVSE and EV

Commercial EV Supply Equipment (EVSE) has to manage payments, negotiate grid charging schedules and authorize the vehicle with which it is communicating. To support that, the EVSE communicates with the EVCC using regular digital communication defined as High Level Communication (HLC) by the ISO-15118. This communication is performed using Powerline Communication (PLC) technology, which modulates digital data over the signal of the CP line. The Homeplug GP defines how to set up a logical network with the Signal Level Attenuation Characterization (SLAC) protocol which is used to identify different entities on the bus. Once complete, IPv6 addresses are assigned on both sides and the vehicle begins a regular ethernet-based communication with the charging station. From this point, the EV and the EVSE are able to exchange messages using the protocols defined by the ISO-15118 or DINSPEC-70121.

After the physical and link layer have been established, the EV sends broadcast messages over UDP to discover the address of the EVSE in the network. This is part of the SECC Discovery Protocol (SDP) which involves a relatively short interaction. Supply Equipment Communication Controller (SECC) is another term used to refer to EVSE in the ISO-15118 standard. The EVSE then replies with the available IPv6 address, which transport protocol to use (UDP/TCP), and whether or not to use TLS. After this phase, the EV queries the EVSE with V2G messages in the process of drawing power from the charging station.

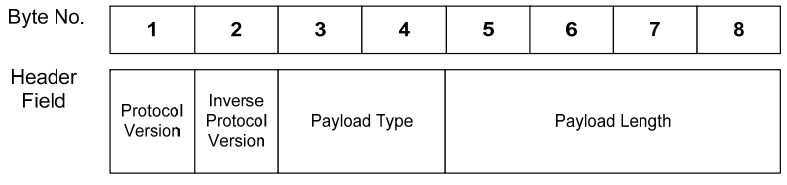

The V2G messages are defined in the ISO-15118 or DINSPEC-70121 and are represented in an XML structure. These XML messages are encoded in a binary format using Efficient XML Interchange (EXI), which serves as an underlying protocol layer in the communication stack. Finally, each V2G message exchanged is wrapped with a transport protocol header of 8 bytes to include payload length, type and protocol version as defined by V2GTP:

Discovery #1 – Buffer overflow in the SLAC implementation in open-plc-utils

Our team discovered a critical stack-based buffer overflow vulnerability in the open-plc-utils project, specifically within its implementation of the Signal Level Attenuation Characterization (SLAC) protocol. This protocol is essential for establishing stable Powerline Communication (PLC) between electric vehicles and charging stations. The vulnerability, tracked as CVE-2025-27071, stems from a failure to validate the “number of groups” field in incoming network packets, which dictates the size of a variable-length array containing attenuation measurements.

In both the EV and charging station (EVSE) implementations, the code extracts this user-controlled value and uses it directly in memory copy operations without boundary checks. Because the destination buffers – such as the session->AAG variable – are allocated on the stack with a fixed size of 58 bytes, an attacker can provide a value up to 255 to overflow the buffer. While the open-plc-utils project had not been updated for over a decade, this flaw remains significant as the tools are still commonly used in Linux-based charging station infrastructures. The issue was reported to Qualcomm in December 2024, leading to a security advisory and a subsequent patch for the open-source project in late 2025.

Charging Station as an IoT Device

The combination of embedded computing power, network connectivity, and user-centric app integration makes charging stations a classic example of an IoT device. Typically running Linux, the EVSEs make use of the stability and flexibility of an open-source operating system to manage the common underlying functions. Typical EVSEs also have various connectivity features to allow the charging stations to communicate with the global internet (Cellular), a nearby user application (WiFi or Bluetooth) or a smart card (NFC).

Until now, these connectivity vectors have been the primary way the security research community has tried to attack EVSEs. Most published security research on EVSEs has focused on exploiting vulnerable services available over WiFi, exploiting known vulnerabilities on the Linux Bluetooth stack and other nearby-communication channels.

Discovery #2 – Remote code execution on charging stations

Our team discovered an integer overflow in the V2G Transport Protocol (V2GTP) implementation of the EvseV2G module of the EVerest framework. This critical vulnerability leads to a heap overflow and allows an attacker to run arbitrary code on the Linux process which can lead to bypassing the payment gate for charging, compromising private keys stored in the charging station (aka EVSE), and communicating with the vendor’s backend using Open Charge Point Protocol (OCPP) by impersonating the compromised, but trusted, charging station.

EVerest is a Linux Foundation-backed open-source modular framework for EV charging stacks. The vulnerability (CVE-2024-37310) we discovered exists in the framework’s V2G Transport Protocol (V2GTP) layer, specifically in how it parses payload lengths. A faulty boundary check fails to account for a 32-bit integer wraparound when adding 8 bytes to the indicated length.

Exploiting this vulnerability, an attacker could provide a malicious payload length (such as 0xFFFFFFFF) that causes an integer overflow during the check. This results in a small value that bypasses the security check meant to limit data to the 8192-byte buffer capacity. Consequently, the system attempts to receive an unlimited number of bytes into a fixed-size heap buffer, leading to a heap overflow. This vulnerability, which has a critical CVSS score of 9.0, allows for remote code execution directly from the charge port.

Distributed Charging Stations Are Often Managed in the Cloud

Setting up a charging station network is inherently different from distributing gasoline to regular distribution points. The distributed charging stations cannot be expected to deliver whatever power the EV demands at whatever time. These parameters have to be negotiated with a central entity. A central backend, often known as a Charge Point Operator (CPO), is used to control the distributed EVSEs in the station using the Open Charge Point Protocol (OCPP). To support the information exchange between the EV and the charging station, the EVSE communicates with the EVCC through digital communication (or High-Level-Communication as defined by ISO-15118) over the Control Pilot pin on the charging connection. The digital data is modulated over a wire using Powerline Communication (PLC) .

Sometimes, the CPO is a private server that physically resides near the gas station it manages. However, we found many cases where EVSEs are connecting to servers that are openly available on the internet, and authentication is only used to verify the backend and not the connecting EVSEs. This allows anyone to query the server and impersonate a charging station to receive data or scan its open ports.

Discovery #3 – Compromising a CPO’s backend cloud server

Our findings revealed a public server that is vulnerable to arbitrary cloud-based attacks that allow attackers to gain managing-level access to these EVSEs.

Research into a manufacturer’s Android app led to the identification of a backend Charge Point Operator (CPO) server that also handled OCPP communications. This server was found to be running the Spring Boot framework with a management feature enabled by default. This configuration is highly insecure as it allows an attacker to access a sensitive endpoint and trigger a full heap dump of the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) that runs the server.

By analyzing this heap dump, an attacker can extract critical information such as proprietary code, passwords, URLs, secrets, organization emails, and the VINs of vehicles that have used the charging stations. The impact is severe because a compromised CPO backend allows an attacker to control managed charging stations, potentially enabling them to manipulate firmware upgrades, dictate power supply levels, or grant free charging across the network.

We immediately informed the owner of the compromised server of the vulnerability and it was quickly addressed.

Compromised EVCC as a Vehicle Theft Vector

The vulnerabilities discussed in this article, which allow for compromise of the EVCC directly through the charge port, open up a new and critical attack vector for vehicle theft. Unlike previous attack methodologies that required an attacker to physically break into the vehicle to gain access to the internal CAN bus, the compromised EVCC provides an external and readily accessible entry point.

The basic attack chain for stealing an EV in such a scenario would be as follows:

- Exploitation via Charge Port: An attacker exploits a vulnerability in the EVCC (such as the buffer overflow or integer overflow discoveries described earlier) from the external charging port. This grants them remote code execution on the EVCC.

- Internal Bus Communication: Once the EVCC is compromised, the attacker can leverage the EVCC’s connection to the vehicle’s internal network to send arbitrary CAN messages onto the vehicle’s bus.

- Vehicle Command Injection: These arbitrary messages can mimic legitimate commands, allowing the attacker to bypass electronic immobilizers and unlock the vehicle’s doors and start the vehicle, effectively stealing it without a key.

This attack is particularly potent because the EVCC, by its function, is a gateway to the internal vehicle network that is exposed to the outside world.

Mitigations for Vehicle Theft via EVCC

To prevent a compromised EVCC from being used as a potential new surface for vehicle theft, we recommend that OEMs take a multi-layered security approach:

- Implement Anti-Exploitation Mechanisms: Ensure the EVCC’s firmware is properly protected with modern anti-exploitation defenses such as stack canaries and Memory Protection Units (MPU) to make the exploitation of vulnerabilities like buffer overflows significantly more difficult.

- Segment the Vehicle Network: Design the vehicle’s network topology to isolate critical ECUs, such as the EVCC, from highly sensitive ECUs that control functions like engine start or door locks. The EVCC should reside on a separate, low-trust domain, and any messages it sends to the high-trust domain must be rigorously filtered, authenticated, and validated by a robust gateway before being forwarded.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The growing adoption of electric vehicles is driving the need for robust charging infrastructure and frameworks. As vendors increasingly rely on existing implementations of the low-level protocols comprising the standard, it is becoming crucial to address cybersecurity concerns inherent in these systems. The vulnerabilities our research team discovered originate from unique attack vectors that extend beyond commonly perceived risks of ECUs and EVSEs as an we’re discussing a new attack vector: The EV Charging Port. This underscores the importance of a comprehensive security approach with an emphasis on penetration testing to ensure the safe and reliable deployment of EV charging stations.

Engineers working in EV charging environments are advised to consider the following steps to mitigate the risk of vulnerabilities similar to those described here:

- Apply the appropriate security controls on ECUs based on the standard and hardware capabilities

- Exercise caution when using 3rd party and open source tools

- CPOs should be implemented with security in mind (e.g., secure endpoints, limit public exposure to OCPP server)

About PlaxidityX Cyber Security Research and Solutions Department

The PlaxidityX Cyber Security Research and Solutions department is a leader in protecting the automotive industry. With a deep understanding of vehicle architectures, protocols, and standards, we provide comprehensive cybersecurity services to our clients.

Our team, backed by decades of expertise in both cybersecurity and the automotive sector, has partnered with major OEMs and Tier 1s on dozens of penetration testing and research projects. Our goal is to verify and strengthen our customers’ cybersecurity posture, helping them meet and exceed key industry regulations like UNR 155 and ISO-21434.

Whether it’s a dedicated research project or the deployment of our advanced PlaxidityX products, we deliver the solutions and insights needed to stay ahead of evolving threats and ensure vehicles are secure throughout their lifecycle.

Published: February 9th, 2026